Writing Comes Hard

Writing comes hard for me. It always has. A part of the problem is that I’m a perfectionist. In September 2004, I enrolled in the Professional Writing program in Michigan State University’s College of Arts and Letters. The professors and instructors were phenomenal, but each gently pointed out that I was a perfectionist. It’s who I am and how I approach life. I believe that personally demanding my best benefits the ultimate consumer of my work product: the reader.

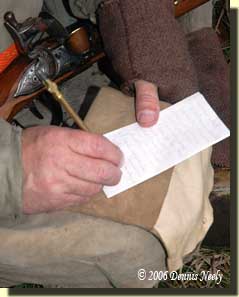

Many of my manuscripts start out as field notes scrawled on loose sheets of paper, folded in half lengthwise, then folded in thirds, creating 12 smaller “pages.” I keep the folded “journal sheets” in a buckskin envelope, along with a brass lead holder, called a “porta crayon.” The idea is borrowed from the 18th-century, British Army “return.” A large sheet of paper was folded following a standard pattern. Each folded page was assigned to record specific information (number of men fit for duty, drills, etc.) about that company’s daily activity. The document was sealed with wax, bundled and returned to the British War Office in England, thus the name, “return.”

Many of my manuscripts start out as field notes scrawled on loose sheets of paper, folded in half lengthwise, then folded in thirds, creating 12 smaller “pages.” I keep the folded “journal sheets” in a buckskin envelope, along with a brass lead holder, called a “porta crayon.” The idea is borrowed from the 18th-century, British Army “return.” A large sheet of paper was folded following a standard pattern. Each folded page was assigned to record specific information (number of men fit for duty, drills, etc.) about that company’s daily activity. The document was sealed with wax, bundled and returned to the British War Office in England, thus the name, “return.”

The process of creating the first draft is the most difficult and might take as long as a week, depending on topic and required research. Sometimes the words flow and sometimes they don’t. Often the details contained in the field notes must be “scaled back,” and at other times, they require another trip to that particular area to gather additional information or check on a pertinent detail.

Research time is a key element in my writing process, not only for the traditional black powder hunting series, which is based on 18thcentury history, but also for the simplest Nature story or a foggy, small-town memory. And for some subjects, the necessary research, documentation or photographic support might take months to accumulate.

Once completed, I like to set the rough draft aside for a few days to “ferment and age.” Waiting gives me a chance to reflect on the piece’s perspective, recall additional details and add afterthoughts. Waiting also affords me the opportunity to view the work anew, like a reader discovering the work for the first time. Discrepancies, inconsistencies and/or mistakes seem to jump off the page. Each time I edit, I try to wield a ruthless pen, thanks to the advice Stephen King gave in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft:

“If it works, fine. If it doesn’t, toss it. Toss it even if you love it. Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch once said ‘Murder your darlings,’ and he was right” (Scribner, New York, NY, 2000, 197).

Please continue to enjoy your visit, be safe, and may God bless you.