Published in Woods-N-Water News: Michigan’s Premier Outdoor Publication: September 2013: Pgs. 80 & 81

A green tree frog dropped on a wet oak leaf. The unexpected visitor landed on its back, stretched its legs and squirmed. Water from a late-night rain squall dripped from half-leafed ironwood branches that curved over my head. The little creature convulsed, then kicked hard with its left hind leg. It didn’t hop, but instead pushed itself under the closest shelter, another palm-sized oak leaf, weathered by a hard winter.

A green tree frog dropped on a wet oak leaf. The unexpected visitor landed on its back, stretched its legs and squirmed. Water from a late-night rain squall dripped from half-leafed ironwood branches that curved over my head. The little creature convulsed, then kicked hard with its left hind leg. It didn’t hop, but instead pushed itself under the closest shelter, another palm-sized oak leaf, weathered by a hard winter.

My buffalo-hide moccasins crossed time’s threshold before dawn. The path to yesteryear proved quick and direct, chosen to avoid an unnecessary soaking. The ironwood overlooked a small clearing in the hardwoods, a favorite strutting ground for an old tom turkey that I had designs on. It was early May, back in 1795, not far from the headwaters of the River Raisin in the Old Northwest Territory.

At first light a hen clucked twice to the east, soft and subdued: “Ark, ark.” I rolled the single wing bone in my fingers, but decided to wait on answering. Deep down I wanted to hear the long-bearded tom’s gobble echo throughout the forest.

To the south, I heard big wings thrash about the time the gray clouds overhead turned pink underneath. The air smelled moist, but felt cool. My ears never detected the hen leaving the roost. I reconsidered the wing-bone call, but again deferred in case she was still perched.

Agonizing minutes ticked away. A female cardinal swooped from somewhere above and landed on the top-most twig of the ironwood. I sat cross-legged on the wool blanket roll; only my eyes moved. It chirped once or twice. I paid little attention until it flitted lower. Curious, I suppose, it cocked its tufted head to one side and chirped over and over, garnering my attention.

I fought to concentrate on the clearing, fearing I might miss glimpsing the gobbler’s cautious approach. The cardinal lingered, and when it gave up asking questions and flew off, I clucked once, “Arrkk.” Save for a few crows in the distance, the forest remained quiet.

About an hour passed. Leaves rustled, followed by a long silence. Another rustle, then silence. Another…silence. My thumb pressed hard on the Northwest gun’s hammer. “A clean kill, or a clean miss. Your will, O Lord,” I prayed.

The last pause proved longest. Convinced the old tom stood behind me well within the death bee’s realm, I eased the trigger back as I pulled the hammer to full cock, avoiding the distinctive click of the sear snapping in the tumbler’s notch.

Another rustle left little doubt the gobbler’s course was to my left. I squinted. My mind rummaged through past experience as I started evaluating possible scenarios for raising the smooth-bored firelock. I felt my arteries pulse as I forced myself to subsist on shallow breaths.

I counted the rustles. At six, movement broke into the corner of my left eye, not two trade-gun lengths distant. The rabbit’s brown, glassy eye appeared huge. Its ears twitched front to back and its nose sniffed. It stopped when my lungs released a hefty portion of used-up air. I chuckled. Unafraid, the cottontail hopped on, attentive to its 18th-century business.

Traditional black powder hunting offers an almost endless assortment of possibilities for enjoying the pursuit of wild game in a historical manner. For example, some folks choose to simply hunt with an old-style black powder arm while wearing the clothing and using the accoutrements of a particular bygone era. For this group, the sights, the sounds, the smells and the feel of the past, coupled with the thrill of meeting the challenges of putting meat on the family dinner table as it was once done, provides sufficient satisfaction and enjoyment.

Others go a bit further, pushed by an insatiable desire to relive every aspect of backcountry life. Traditional hunters in this group create a “persona,” or characterization of someone from the past, based on either a person who once lived or a composite of known individuals. Taking on a persona allows the participant to focus on a broader range of details specific to a geographical region, station in life and time period. In addition, following this path leads to a greater understanding of everyday life—for me, in the 1790s.

Several years ago I read Joseph Ruckman’s book, Recreating the American Longhunter: 1740-1790. One passage in particular kept haunting me, because it showed the importance of one’s persona displaying a well-rounded assortment of woodland skills:

Several years ago I read Joseph Ruckman’s book, Recreating the American Longhunter: 1740-1790. One passage in particular kept haunting me, because it showed the importance of one’s persona displaying a well-rounded assortment of woodland skills:

“…I want to dispel the myth that the longhunters spent all their time hunting or among the Indians. Those whom we remember best as longhunters—i.e., Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton, the Cresaps, and the Gists—were primarily farmers, and to a slightly lesser extent, cattlemen and herdsmen. Hunting and exploring were essentially sidelines, and dealings with Indians were more often than not of a hostile nature. The point is, if you want to portray a believable longhunter, you should know something about farming…” (Ruckman, Joseph, Recreating the American Longhunter: 1740-1790, Graphic/Fine Arts Press, Excelsior Springs, MO, 2000, pg. 7)

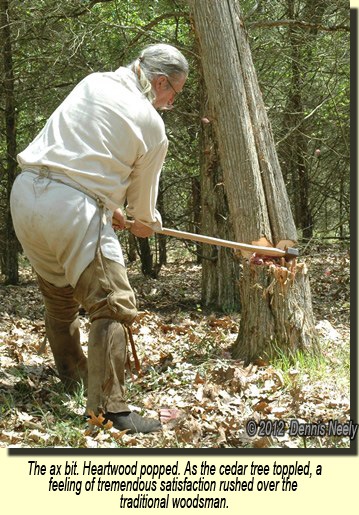

I sat for about an hour after the cottontail rabbit hopped by, then my traditional black powder hunt took an educational detour. I returned to a makeshift hunting camp and retrieved a forged-iron, single-bitted ax. With the ax in my left hand and the Northwest trade gun in my right, I returned to my 18th-century business—cutting back the wagon trail.

The management plan for the property includes periodic maintenance of a two-track road I call “the wagon trail” in my traditional hunting journal. In 2009 we determined that 50-years of slow growth needed to be trimmed. A white “X” marked a number of red cedar trees, all about eight inches in diameter.

Now most moderns would fire up a chainsaw and make short work of the project, but those of us who prefer to frolic in yesteryear view the circumstance differently. For the traditional woodsman, the cedar trees are not a trashy invasive species, but rather afford an opportunity to clear land as our forefathers did and experience the grittier side of one’s persona.

I began researching felling axes. Commissioning a hand-forged copy of an original ax was one choice, but I feared a gray-haired woodsman’s arthritic limbs might not be up to the task. While debating the investment, I literally stumbled over a pail of rusty old single-bitted ax heads at an outdoor flea market. After scrounging through the bucket, I paid a dollar for a pitted, well-used head with a peened-over poll that appeared hand-forged.

Keeping my buffalo-hide moccasins firmly planted in May of 1795, I leaned the Northwest gun against a small cedar tree and hung my shot pouch and powder horn over the firelock’s muzzle. I untied the woven sash about my waist, folded it over a branch, removed my linen hunting shirt and draped it over the sash.

Four steps away, swift blows of my tomahawk sliced the lower branches from a cedar tree, cleaning the trunk head high. A southwest breeze whispered through the tree tops as the felling ax bit hard on the trunk’s east face.

“Thuuup…thuuup…thuuup… thuuup…” Creamy-yellow sapwood chips flew. After a half-dozen swings, the air smelled of wet cedar. Moisture oozed into the growing felling notch. With each hearty strike, my moccasins slipped in the dry oak leaves. The unmistakable sound of steel biting timber echoed along the wagon trail. Sweat beaded on my brow, then trickled into my eyebrows. “Thuuup…thuuup…thuuup…”

“Thuuup…thuuup…thuuup… thuuup…” Creamy-yellow sapwood chips flew. After a half-dozen swings, the air smelled of wet cedar. Moisture oozed into the growing felling notch. With each hearty strike, my moccasins slipped in the dry oak leaves. The unmistakable sound of steel biting timber echoed along the wagon trail. Sweat beaded on my brow, then trickled into my eyebrows. “Thuuup…thuuup…thuuup…”

I forced myself to stop, wiped away the sweat with the back of my hand and looked about as I experienced a moment of trepidation. In the silence of the forest, I felt a concern for my safety. Was I alone? Had someone else heard the ax? I rested within an arm’s reach of the leaning smoothbore.

At first, I lacked control of the blade. The slanted cuts were erratic, but with each swing the ax’s curved blade struck closer to the previous gash. It took over two hours to fell that first cedar tree. My skill improved, and after eight or nine cedars, the felling time dwindled to about thirty minutes.

The lessons are ongoing in the wilderness classroom, but I can speak with firsthand knowledge of clearing land and falling trees with an ax. From the numbing fatigue to the spirit-raising joy, I have lived a small portion of the backcountry hunter’s life, a part mentioned on occasion, but rarely experienced.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.