Published in Woods-n-Water News: Michigan Premier Outdoor Publication: April 2015: Pgs. 56 & 57

“Gather ‘round everybody,” Alan Hoeweler half-yelled from beneath a faded-green popup canopy erected on the sun-side of a tree-lined dry creek. Khaki-clad shooters in Victorian or Edwardian clothes, some wearing pith helmets, straw hats or Indiana-Jones-style Fedoras, set their prized muzzleloaders on tailgates and walked to the north end of the makeshift parking area.

“Welcome to today’s double rifle shoot,” Hoeweler continued. He wore the range officer’s customary blaze-orange baseball cap and squinted through yellow-lensed safety glasses. “We want everybody safe. Cap or prime only between the posts, and hearing and eye protection are highly recommended.”

“We’ve got the ‘big five’ game targets from Africa waiting for you, a charging water buffalo and some knock-down targets, too. You shoot two times at each station with 50 points per hit. Bonus shots are interspersed throughout the course; shooter’s choice up to two shots each with a hit worth 25 points, but if you miss, we subtract 25 points. Then we go to the knock-down targets. A hit’s worth 25 points, and a complete knock down gets 50 points. You get two shots at the charging water buffalo with 50 points per hit.”

“We’ve got the ‘big five’ game targets from Africa waiting for you, a charging water buffalo and some knock-down targets, too. You shoot two times at each station with 50 points per hit. Bonus shots are interspersed throughout the course; shooter’s choice up to two shots each with a hit worth 25 points, but if you miss, we subtract 25 points. Then we go to the knock-down targets. A hit’s worth 25 points, and a complete knock down gets 50 points. You get two shots at the charging water buffalo with 50 points per hit.”

“As most of you know,” Hoeweler continued, “this is not an official match yet. We have to hold three shoots with descent attendance to become a regular match, which will happen next June.”

A little after noon on a bright and warm Sunday in mid-September, cars and trucks rumbled up Caesar Creek on the home grounds of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association in Friendship, Indiana. Past Shaw’s Quail Walk and the Herman Marker Skeet range, the limestone two-track narrowed. At a break in the sycamores and maples, vehicles pulled up a steep drive and into an open clearing divided lengthwise with yellow and black caution tape strung between hastily-driven wooden stakes.

Like most black powder shooting events, old friends greeted old friends, and strangers and interested bystanders soon became new-found friends. The growing crowd milled about, all hashing over the intricacies of a specific class of black powder guns that achieved legendary status on 19th-century safaris in far off Africa.

“They made these guns for hunting in Africa and India,” Harold Wade said holding out a walnut-stocked, double-barreled percussion rifle to a spectator. “When the double rifles went to black powder cartridge, Purdey (James Purdey & Sons, Ltd., London) called them ‘Express Rifles.’

“This is a John Rigby (John Rigby & Company, Ltd., London), .451-caliber double gun from about 1860. I’ve owned it about five years. I traded a Rigby target rifle with Rick (Weber) ‘cause he needed a target rifle and I wanted a double rifle.”

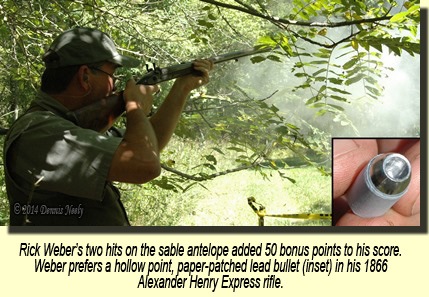

“Every time I see the double Rigby I want to swap back,” Rick Weber added with a whimsical twinkle in his eye. Weber cradled an original Alexander Henry .451-caliber express rifle made in Scotland in 1866. “The gun came with the case it was originally shipped in.”

“Some of these guns shot a ‘winged bullet,’ which was a conical bullet with two little knobs cast off the sides,” Don Kettelkamp explained. “They did that because the British rifling was too fast. They put the wings on so the bullet wouldn’t strip out of the rifling as it traveled down the bore.

“Harold (Wade) has a double Whitworth rifle with a hexagonal boring and a 1-in-20 twist (the bullet makes one complete revolution in 20 inches),” Kettelkamp added. Wade said the Rigby has a 1-in-22 twist, and Weber’s Henry rifle is 1-in-24.

“I shoot a solid-point lead bullet that weighs 310 grains,” Wade said. “The bullet measures .441 (of an inch diameter) with a paper patch made from nine-pound, 100-percent cotton paper, lubed with a special black powder lube. I weigh out each powder charge of 2Fg Olde Eynsford black powder by Goex (for accuracy).”

After each marksman signed up and paid the entry fee, Hoeweler divided the competitors up into groups of four shooters each. To save time, each group started at a different station.

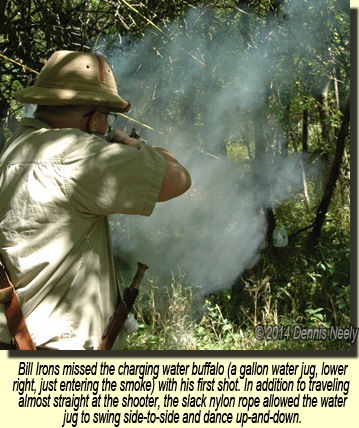

Harold Wade, Rick Weber, Bob Conrad and Bill Irons walked to the far north end, then turned right into a lush thicket where an empty plastic water jug hung suspended from a continuous nylon rope. A pulley and crank system, operated from behind the shooting station, propelled the jug almost straight at the competitor from about 25 yards out.

“Ya gonna live through this one?” Bob Conrad asked with a grin.

“Who knows? I’m just going to rear back, take aim and have fun,” Weber replied as he cocked both hammers on the Henry express rifle. “Pull it!”

The water jug bounced up and down from slack in the line. At 20 yards the Scottish double’s right barrel roared with a long fiery tongue. White smoke obscured the charging water buffalo. The left barrel thundered. The beast broke through the smoke, bobbing from side to side, striking Weber in the left shoulder when it passed.

“I got gored,” Weber said with a broad smile.

A life-size sable, standing broadside partway up a wooded hill, offered bonus points. But to see the “vitals,” a steel clangor suspended behind a six-inch hole in the plywood silhouette, each shooter had to duck under a walnut sapling’s low branches. Interspersed with a hefty amount of good-natured kidding, Weber’s two hits earned “some redemption” and 50 points.

A life-size sable, standing broadside partway up a wooded hill, offered bonus points. But to see the “vitals,” a steel clangor suspended behind a six-inch hole in the plywood silhouette, each shooter had to duck under a walnut sapling’s low branches. Interspersed with a hefty amount of good-natured kidding, Weber’s two hits earned “some redemption” and 50 points.

On that day’s safari to darkest Africa, a rhino appeared in the shadows at 60 yards. Splotches of sunlight hid the point of aim from Harold Wade. “There’s leaves in front of it, to the upper right,” Alan Hoeweler said after joining the group to check on their progress.

A lion lurked at 40 yards, a zebra stood in full view at 30 yards, then a long-horned oryx seemed unaware as the entourage loaded from their safari pouches. Wade and Irons both scored two hits on the large antelope. At 65 yards an elephant faced straight on, eliciting a noticeable hush among the hunting party.

Four resettable, knock-down steel targets, each about six inches square and standing knee-high on a pair of hinged, angle-iron legs, offered the next challenge. “There’s a fine line between knocking them down and just hitting them,” Bob Conrad said as he capped his left barrel. Conrad’s first shot hit with a metallic thud. The black square tipped away with noticeable hesitation as if it might flip back up, then it fell over. “See what I mean?”

Down the line, the hunting party encountered a black Cape buffalo veiled by the dark shadows of three sycamore trees. The final encounter was with a crouched leopard up on the hillside.

At the initial group meeting, Hoeweler had explained that the leopard was shot from the sitting position, as if the hunter was seated on a river steamboat. For safety, the boat’s seat, a steel folding chair, sat on a sheet of plywood. Seeing the leopard, let alone finding the vital spot, proved difficult as each hunter fidgeted and turned back and forth in an attempt to get a clear sight picture.

At the end of the afternoon, both competitors and spectators came away with an inkling of the flavor and texture of a bygone African big game safari. The original, muzzleloading rifles used in this match added to that aura, for each came with its own history, its own pedigree. The full-size targets, hand-painted to resemble living animals, placed in true-to-life settings added to the ambiance, too. And the match sponsors’ emphasis on wearing the Victorian or Edwardian clothing of long ago contributed to the overall impression that “we were there.”

“Being safe comes first, of course,” Harold Wade said as Alan Hoeweler tabulated the scores, “but shooting these old rifles, sharing in the fellowship and camaraderie, taking part in the kidding and having fun are what’s important. And if you win, it’s a bonus.”

Give the black powder shooting sports a try, be safe and may God bless you.