Published in Woods-N-Water News: Michigan’s Premier Outdoor Publication: October 2014: Pgs. 60 to 62.

A plump bat swooped low. The little beastie veered side to side, up then down. It circled within the stifling humidity of the log cavern, once, twice, three times, then flew straight up and grasped the underside of a rough-hewn rafter. Appearing a bit perplexed, it looked down at the humble souls trudging up the stairs in resolved silence. The bat scrambled up the rafter’s west side and huddled close to a roof plank. With an attack imminent, my alter ego wondered, “What shall I do?”

A plump bat swooped low. The little beastie veered side to side, up then down. It circled within the stifling humidity of the log cavern, once, twice, three times, then flew straight up and grasped the underside of a rough-hewn rafter. Appearing a bit perplexed, it looked down at the humble souls trudging up the stairs in resolved silence. The bat scrambled up the rafter’s west side and huddled close to a roof plank. With an attack imminent, my alter ego wondered, “What shall I do?”

Hunt-stained elk moccasins shuffled into the darkest recess of the chamber’s east corner. My shoulder pressed light against a dirty log. From there, like the displaced bat, I, too, took measure of the others. I did not know whom to trust and did not wish to suffer a knife plunged into my back or feel the wrath of a tomahawk upon my temple because a settler thought I was more Indian than white.

In all, eighteen souls climbed those stairs, including the wife of a man named Rosemeyer. She did not dress as a proper frontier lady, but rather wore a sweat-stained buckskin skirt and a sun-faded brown trade shirt. A wicked long knife hung from her leathern belt in the small of her back. Gobbler spurs mixed with red and blue beads strung on a hemp cord served as her hatband. I overheard the Colonel say she shot a rifled gun better than most men.

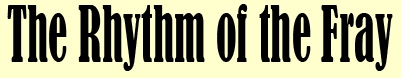

The stagnant air smelled of old dust and the perspiration of hard labor. With haste the Colonel explained the order of fire and assigned the gun ports, and just as he finished, the attack began with a whoop and a holler. Sun streamed through the break in the logs three shared: Jeff Pell, a grizzled rifleman; Ned Newhart, a hardy settler; and Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox, a white returned captive who could not forsake the woodland ways of the Ojibwe who raised him.

The stagnant air smelled of old dust and the perspiration of hard labor. With haste the Colonel explained the order of fire and assigned the gun ports, and just as he finished, the attack began with a whoop and a holler. Sun streamed through the break in the logs three shared: Jeff Pell, a grizzled rifleman; Ned Newhart, a hardy settler; and Msko-waagosh, the Red Fox, a white returned captive who could not forsake the woodland ways of the Ojibwe who raised him.

Priming flashed, rifles cracked and an occasional smoothbore belched a fiery tongue with more of a “BOOM!” than a “BANG!” White, sulfurous smoke obscured the gun port. My alter ego, Msko-waagosh, felt no remorse taking aim at the British soldiers, but a gnawing fear twisted his gut, seated in the realization that Native allies might be among the Redcoats advancing on the fort.

Newhart shot, rose to his feet and stepped to the right while Pell started a patched ball with a judicious push of his knife’s handle. The Northwest gun’s muzzle poked through the opening. Gunpowder cascaded into the open pan. The English flint snapped to attention. The back of my hand steadied the forestock on the log sill. The turtle sight found the white straps that crossed a Redcoat’s chest, then eased two-hands-width higher. “Kla-whoosh-BOOM!”

In the rhythm of the fray, the smoothbore’s smoking barrel withdrew from the opening as I arose from kneeling. I stepped right. Pell shoved his longrifle’s muzzle through the gun port.

The powder measure was but a dark shape in the log cavern’s smoky dimness. I felt the precious granules spill over onto a finger. The bat circled once, twice, then returned to the rafters. The charge tumbled to the breech. A bare death messenger clattered close behind. Pell’s pan erupted with a blinding flash. The rifle cracked. His lips mouthed “got one” as he turned away.

A steady finger pushed a hunk of wadding into the Northwest gun’s hot muzzle. The wiping stick rattled as it rammed the load tight. The settler took aim as I glanced up. The last foot of the stick slipped into the trade gun’s ribbed brass thimbles. Newhart’s rifle barked: “BANG!”

That afternoon, in the summer of 1795, Red Fox entered the fort’s trading house. Four prime buckskins purchased two handfuls of gunpowder and thirty round balls. The trader tried to tempt the woodsman with a new knife, a pipe tomahawk, then a dozen gun worms, but to no avail.

That afternoon, in the summer of 1795, Red Fox entered the fort’s trading house. Four prime buckskins purchased two handfuls of gunpowder and thirty round balls. The trader tried to tempt the woodsman with a new knife, a pipe tomahawk, then a dozen gun worms, but to no avail.

Wearing “Indian dress”—buckskin moccasins, a breechclout, a ruffled trade shirt and a woven wool sash tied about his waist—the returned captive walked through the doorway and into the commons amid questioning stares and suspicious looks. Before Msko-waagosh could slip away, a disheveled farmer appeared in the clearing between the blockhouse and forest, running hard and shouting, “British! British soldiers!”

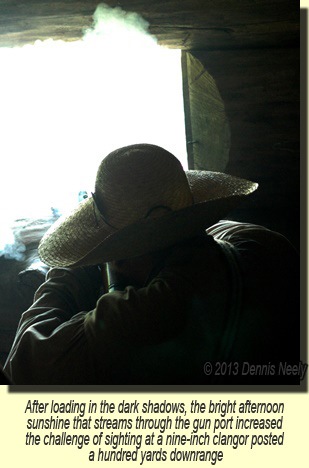

Minutes later, Colonel Roberts took charge, ascending to the top tread of the blockhouse steps. Even without a proper weskit over his clean white shirt and faded-green knee breeches, the Colonel looked formidable. A stately blue-silk scarf was tied about his neck, and his cowhide leggins were buttoned and belted. “Grab your firelocks, horns and pouches and head upstairs,” he ordered as he turned to his right and stared straight at me, stern and uncertain. With no choice, I obeyed.

Traditional black powder hunting offers a myriad of paths to what once was. On a beginning level, individuals can gain a representative taste of our rich American hunting heritage simply by donning the leather and linen garments of a bygone era, taking up a black powder arm and engaging in a fair-chase pursuit—be it gray squirrels, wild turkeys or white-tailed deer.

The distinctive sound of a firelock, the sight of a yellow tongue of flame, the pungent smell of spent black powder, the taste of jerked venison and the unusual feel of a trade shirt, knee breeches and wool leggins all combine for an unbelievable outdoor memory.

After a few traditional hunts, historical thoughts and reflections fling open antiquity’s door and usher a curious time traveler back to a deeper, more meaningful experience. In my case, the quest became addictive, driven by an all-encompassing question: “What was it really like to live, hunt and survive in the Old Northwest Territory?”

In the mid-1990s a group of living historians sat around a campfire on the home grounds of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association in Friendship, Indiana. Someone wondered out loud if it was possible to re-create the conditions of a frontier fort under attack, allowing the defenders to respond with live rounds. The discussions grew serious, and in June of 1999 the first “Fort Greenville Match,” named to honor the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, was held, utilizing the two-story log blockhouse on the Max Vickery Primitive Range.

In the mid-1990s a group of living historians sat around a campfire on the home grounds of the National Muzzle Loading Rifle Association in Friendship, Indiana. Someone wondered out loud if it was possible to re-create the conditions of a frontier fort under attack, allowing the defenders to respond with live rounds. The discussions grew serious, and in June of 1999 the first “Fort Greenville Match,” named to honor the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, was held, utilizing the two-story log blockhouse on the Max Vickery Primitive Range.

Flintlocks, either rifles or smoothbores, and period-correct clothing are required for this historical shooting competition. Three-person teams are chosen by drawing lots. The safety rules are strict. Firelocks are loaded only on the range officer’s command, and the muzzle must be through the window and pointed downrange before the pan is primed. The match is timed, usually five minutes. The object is to load and fire as many times as possible. The targets vary and are posted at 80 to 100 yards.

This past June, the Fort Greenville Match presented a tremendous opportunity to add another “life experience” to my emerging returned white captive persona—Msko-waagosh. Ricky Roberts coordinates the match. He is an original member of the founding group, and on that day the historical me chose to elevate him to “Colonel Roberts.”

The journal of John Tanner tells of traveling to the Mouse River trading house and bartering skins for gunpowder and thirty round balls—an event that gave Msko-waagosh a reason for being at the blockhouse. Tanner also speaks of the perils, threats and personal injuries he endured because of his circumstance, including surviving a tomahawk blow to the head and a musket ball that shattered his right arm.

Some returned white captives, like Tanner, found themselves trapped between two cultures. Upon arrival, my outward appearance drew some stares and a few questioning looks, because I was the only participant wearing “Indian dress,” the rest portrayed longhunters, voyageurs or colonial militia. The uncertain glances added a distinct feeling of distrust. An acute awareness of “not fitting in” washed over me, nurturing an 18th-century mindset that approached that described by Tanner.

Somber participants climbed the stairs single file. By choice, my alter ego hung back. Deeply conflicted, the returned white captive crossed eternity’s threshold by the top step. Then, when Colonel Roberts hollered “commence firing,” Msko-waagosh found himself thrust into the frontier turmoil that gripped the Old Northwest Territory.

Somber participants climbed the stairs single file. By choice, my alter ego hung back. Deeply conflicted, the returned white captive crossed eternity’s threshold by the top step. Then, when Colonel Roberts hollered “commence firing,” Msko-waagosh found himself thrust into the frontier turmoil that gripped the Old Northwest Territory.

Loading, taking quick aim and releasing another death messenger was all that mattered, save a fleeting concern that Native allies might be among the British advancing in the clearing. Heartbeats raced. Smoothbores thundered. Rifled guns cracked. A displaced bat swooped. Pungent, roiling smoke choked. Then Colonel Roberts yelled, “Cease fire!”

And out of it all a pristine 18th-century memory emerged, a tale to share in the dancing light of an evening fire, an impression born out of the rhythm of the fray.

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.