Published in Woods-N-Water News: Michigan’s Premier Outdoor Publication: October 2015: Pgs. 60 & 61

Death lurked in the wooded shadows. A canvas-clad leg bent, then eased forward. After a long pause, a piercing sliver of brilliant sunlight illuminated a thick-soled elk moccasin’s subtle advance. Canada geese winged silent overhead, bent on the River Raisin’s lily-pad flats, three ridges to the west. Melted frost dripped from warming cedar bough tips. Now and again, a whiff of drying oak leaves perfumed the glade on that late October morn, in the Year of our Lord, 1762.

The ghostly shape of Lieutenant Lang, an experienced hunter for Captain Hopkins’ British Rangers quartered at Fort Detroit, slipped through the shadows cast by the cedar trees that dotted the long, meandering ridge crest. Near a broken-down red oak, the woodsman’s course dropped lower on the hillside. At a promising trunk, a gray blanket, bound in a roll by hemp rope and a leathern tumpline, settled in the leaves.

The ghostly shape of Lieutenant Lang, an experienced hunter for Captain Hopkins’ British Rangers quartered at Fort Detroit, slipped through the shadows cast by the cedar trees that dotted the long, meandering ridge crest. Near a broken-down red oak, the woodsman’s course dropped lower on the hillside. At a promising trunk, a gray blanket, bound in a roll by hemp rope and a leathern tumpline, settled in the leaves.

“I sat for quite a while,” Lt. Lang reported, “but didn’t see anything, not even a deer. The sun was not quite noon-high when I returned to the trail and followed it west. I came to a steep slope, and as I stood, I saw a couple of birds (wild turkeys) heading to the thicket on the left.

“Rather than pursue, I continued on to a nearby clearing. My hunting companion said he might range to the west side of that opening. I did not wish to intrude or disrupt my partner’s hunt, so I circled back around to the ridge and retraced that morning’s course.

“Forty yards from where the trail breaks out into the opening and follows the edge of the swamp, I spotted a gray head beyond the gentle roll of the hill. I stopped, cocked the fowler and began to bring it to my shoulder. I believed the bird was sitting, pulled close to the ground, either resting or hiding.

“Other turkeys stepped out of the trees. Some walked to the right and a couple hunched down and disappeared to the left. The British fowler’s butt pressed against my shoulder…” Lt. Lang later said.

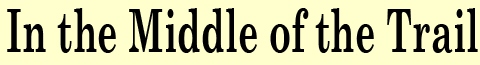

The thought of chasing wild turkeys on a cool October morn is often overlooked by many modern outdoor enthusiasts. Grouse, woodcock, squirrels, pheasants, ducks, geese, bear and white-tailed deer vie for the limited time most sportsmen and women have to devote to the fall hunting seasons. But for many traditional black powder hunters, that is not the case.

Traditional black powder hunting offers a unique blend of America’s rich historical heritage, arms that use black powder as a propellant and fair-chase hunting. Traditional woodsmen, like Darrel Lang, might choose to hunt as a British ranger in the last days of the French and Indian War, or a lover of classic, breech-loading, black-powder-cartridge, double-barreled shotguns might hunt in the wool and canvas typical of his or her great grandfather’s era, the turn of the 20th century. In either instance, the driving force is the same: an honest attempt to re-create the simple pursuits of a bygone era.

Prior to Michigan’s settlement years in the early 19th century, wild turkeys appear in a broad array of narratives as a food source—along with ducks, geese, deer, bear and elk. For living historians who wish to re-create an 18th-century traditional hunt, Michigan elk are a “by-chance-only” possibility. However, white-tailed deer and black bear present doable options (Lang has taken both as a British ranger on patrol), and a wild turkey, bested either in spring or fall, ranks third in period-correct opportunities.

“That morning I was hunting wild turkeys in October of 1762,” Darrel Lang later said. “That put my partner and I in the woods before Pontiac’s Uprising in 1763 and the Siege of Fort Detroit. Based on my research, I feel that during his uprising a British ranger wouldn’t be out hunting, especially that far, but would try to avoid the hostility of the Natives. That’s why I chose that hunting situation set during a peaceful time, rather than during war time.

“That morning I was hunting wild turkeys in October of 1762,” Darrel Lang later said. “That put my partner and I in the woods before Pontiac’s Uprising in 1763 and the Siege of Fort Detroit. Based on my research, I feel that during his uprising a British ranger wouldn’t be out hunting, especially that far, but would try to avoid the hostility of the Natives. That’s why I chose that hunting situation set during a peaceful time, rather than during war time.

“I hunt out of Fort Detroit. I’m not sure how far out the British would have sent patrols. I doubt they would have ranged out to the headwaters of the River Raisin, but there is no evidence, either way. There were plenty of waterways, and patrols stayed out overnight, but I’ve never come across how far out they went.

“British rangers out of Detroit are mentioned quite a lot during Pontiac’s Siege. Rangers were a specialized group. Captain (Joseph) Hopkins, his officers and a company of about 110 independent rangers came to Detroit in the early fall of 1762. Major (Henry) Gladwin didn’t have the food or supplies to feed the rangers. Hopkins picked twenty-some men to stay and sent the rest of the company back to Fort Niagara. My persona is based on one of those who stayed,” Lang explained.

Dedicated traditional black powder hunters like Darrel Lang attempt to re-create, and then take wild game with, authentic clothing, arms and accoutrements, based on historical documents, period paintings and/or illustrations and existing museum artifacts.

In the style of backcountry British military units, Lang wore center-seam elk-hide moccasins fashioned after a French-and-Indian-War moccasin recovered at Fort Ligonier in Pennsylvania. Faded green canvas gaiters covered his lower legs to above the knee. Thin, buckled belts secured the gaiters over his linen, broad-fall knee breeches. A linen outer shirt protected his upper body. Under that, Lang wore a light wool trade shirt and a linen weskit, or sleeveless waistcoat, all as described in literature dealing with British ranger attire.

A leather belt bound the outer shirt tight about his midsection. Lang tucked a hand-forged “early European hunting knife,” the razor-sharp edge protected by a leather sheath, in the belt’s left side. A small belly pouch, copied from images of those used by Rogers’ Rangers, hung from the belt’s center. And in the back, the belt secured the haft of a blacksmith-forged, polled tomahawk, slipped in at a comfortable angle.

A buckled, harness-leather strap, slung over the woodsman’s left shoulder, held a leathern shot bag snug under his right arm. A finger-width, separate strap suspended a replica of a F&I War powder horn over the shot bag and tight to his armpit. Scrimshawed, mid-18th-century-style lettering on the horn’s cream-colored body declared: “Lt. Darrel Lang his horn October AD 1755.”

Green wool covered a museum-quality tin canteen. With a simple hemp-rope strap over the right shoulder, the tiny vessel carried sufficient fresh water for a day’s foray. A leather tumpline with braided-rope tails bound the thick, wool half-blanket, a reproduction of an existing artifact. And because modern wild turkey hunting regulations do not require hunter orange garb, Lang chose an olive-green, hand-sewn workman’s cap with a folded-up linen lip, stained from countless ranger patrols, battles and hunting excursions.

Lang’s muzzleloader was a British-style, smooth-bored, flintlock fowler, reproduced after a 1750-era original. “They were built using different parts of that time. Mine has a copy of a Dutch fowler barrel; it’s an 11-bore, 46-inches (long), octagon to round. It has an English style flintlock, brass trigger guard and rammer pipes. The butt plate is off a Queen Anne musket. There’s an oval, silver thumb piece on the wrist, some simple carving around the barrel tang and trigger guard and simple engravings on the butt and side lock plate. And it patterns great for turkeys.”

Lang’s muzzleloader was a British-style, smooth-bored, flintlock fowler, reproduced after a 1750-era original. “They were built using different parts of that time. Mine has a copy of a Dutch fowler barrel; it’s an 11-bore, 46-inches (long), octagon to round. It has an English style flintlock, brass trigger guard and rammer pipes. The butt plate is off a Queen Anne musket. There’s an oval, silver thumb piece on the wrist, some simple carving around the barrel tang and trigger guard and simple engravings on the butt and side lock plate. And it patterns great for turkeys.”

Outfitted and armed as a British ranger serving under Cpt. Hopkins, his mind swirling with the rich history that surrounds Fort Detroit and driven by a passionate desire to experience the texture of life in a long-forgotten era, Lt. Lang stepped through time’s portal and still-hunted into the harsh wilderness of 1762…

“…a big hen stopped to my right,” Lang continued, “but she was too far for the fowler. Then the head of the one that sat in front of me stretched high. I could see feathers on its neck. I took a bead, squeezed the trigger and the fowler roared. I couldn’t see the turkey for the smoke, so I rushed ahead. I think some of the other turkeys flew off. A fine young jake lay in a pile of feathers in the middle of the trail.”

Give traditional black powder hunting a try, be safe and may God bless you.